In international solidarity activism, chance encounters can lead in unexpected directions. I first met Inge Arnold when I was just starting out as a PhD student, travelling to Canberra to take part in a graduate student workshop at the Australian National University. A mutual friend from the environment movement introduced us because I was heading to Japan and Inge had lived and organised there. Organising among anti-war activists in Hakodate in the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido in the lead up to the Iraq war, Inge helped organise and took part in the International Peace Pilgrimage—an eight-month walk for peace across Australia and Japan that sought to draw connections between experiences of nuclear harm in Australia and Japan. It was an inspiring journey that, I later learned, played a formative role in the lives of many of the leading anti-nuclear activists I was meeting in Australia.

At that time, back in February 2011, the focus of my research was the precarity movement in Tokyo. I was in Canberra to talk about the Freeters’ Union, a group of mostly younger activists organising industrially among the growing pool of casual, part-time, and contract labourers in Tokyo known as ‘freeters’.1 Little did I know that one month later, the Great East Japan Earthquake would shake the world and trigger a nuclear disaster. The shockwaves flowed through to my own research, changing its direction, and drawing me into the vibrant post-Fukushima anti-nuclear movement. It took me more than a decade to catch up with Inge again, when I interviewed her in her new home in Far North Queensland. In the meantime I embarked on my own transpacific activist journey. The similarity of the paths we trod meant I ended up meeting many of the people who had supported the International Peace Pilgrimage. When my research focus shifted to the transnational connections between Australia and Japan, I knew that the International Peace Pilgrimage would have to become part of the story.

In this essay and those that follow, I share stories about the walk pieced together from interviews and from the ephemeral traces it left on the early internet. I hope I can convey a sense of the walk as a physical manifestation of the transpacific solidarity movement at the heart of this series, and of how it shaped the subjectivities of those who took part. Like so much of what I try to capture in this series, the IPP and its impacts are nebulous. Difficult to pin down and difficult to evaluate. We’ll never know what difference a group of tired, and footsore activists made standing outside the gates of a disused uranium mine, or marching down a lonely stretch of highway. But we can see that the experience shaped their lives forever and how, in turn, their lives have continued to shape the world around them as part of an ongoing collective struggle.

The International Peace Pilgrimage

The ‘International Peace Pilgrimage – Roxby Downs to Hiroshima & Nagasaki’ (IPP) took place over eight months from December 2003 to August 2004. It involved a small group of people walking across Australia and Japan and visiting sites associated with the nuclear industry to highlight the ways in which nuclear things have shaped relations between the two countries. The walk formed a part of a broader movement of peace walkers called ‘Footprints for Peace’. As the walkers visited sites of nuclear harm and met with survivors, their dusty footprints traced an historical-geographical map of the nuclear age, in both military and civilian guise, connecting Australia and Japan. Participants included anti-nuclear and peace activists, Indigenous people with roots in Australia, North America and Japan, and members of the Nipponzan Myōhōji Buddhist order. Some of the walkers joined for a day, or a week, or a month. A hardy few walked for the whole eight months. Others didn’t walk at all but joined their footprints with those of the walkers as supporters, providing food, shelter, and other forms of support, welcoming the walkers as they passed through their home towns, sharing stories of survival, and of their struggles against the nuclear industry.

The walk commenced at the gates of the Olympic Dam uranium mine in Roxby Downs in December 2003. From there it traversed the former nuclear testing grounds of the South Australian desert, continuing across Victoria and New South Wales to the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra where, in April 2004, the Australia leg came to a close. From there the walkers flew to Japan, where they travelled down the Pacific coast from Sapporo, visiting nuclear sites located there before crossing the mountain ranges of northern Honshu, Japan’s main island, to the west coast. They traversed the ‘Nuclear Ginza’ of Fukui prefecture, a region that hosts the greatest concentration of nuclear reactors in the world. Finally, they reached Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where they were honoured guests at the annual commemorative events that are held in both cities in August to mark the dropping of the nuclear bomb in 1945.

The International Peace Pilgrimage (IPP) took place at a time when nuclear advocates were talking up the potential for a nuclear ‘renaissance’. As the realities of the climate crisis became harder to deny, nuclear energy proponents were seeking to position the technology as a carbon-neutral source of electric power.2 The walkers rejected this claim and countered it by pointing to the environmental harms that occur across the nuclear fuel cycle. The IPP was rooted in an anti-nuclear tradition that saw both nuclear weapons and power generation technologies as indivisible parts of a destructive nuclear fuel cycle. Tim Collins summarised the participants’ wide-ranging concerns in the activist newspaper Green Left Weekly that:

Today, the nuclear industry is expanding at a more rapid rate than ever before. The forms it now takes are as diverse as they are insidious. Uranium mining continues, more nuclear reactors are being built, food is being irradiated, depleted-uranium weapons are used indiscriminately and there are more nuclear weapons being produced than ever before.3

The walkers drew a direct connection between the nuclear bombing of Japan in 1945 and the harms caused by nuclear testing and uranium mining on Indigenous peoples:

Almost sixty years have passed since the world was horrified by the destructive force of the Atomic Bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is also fifty years since the atomic tests on Indigenous peoples land at Maralinga and Emu Fields, Australia, along with the thousands of other test carried out around the world.4

Walking the Cultural Geography of the Nuclear Age

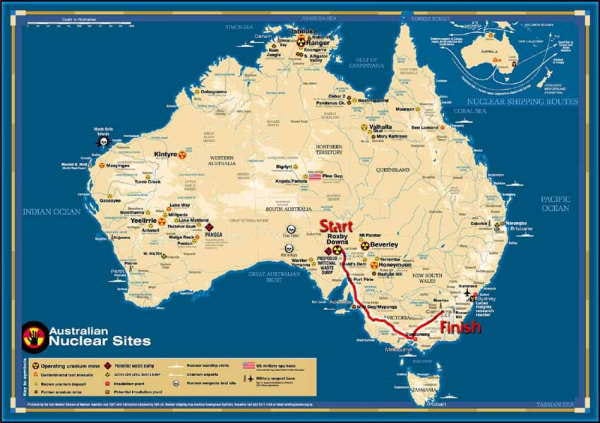

Figure 1 shows the route the International Peace Pilgrimage took across southern Australia, from Roxby Downs to the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra, marked in red. The route is superimposed over a map of Australian nuclear sites that was originally produced by then Western Australian Greens Senator Scott Ludlum and the Anti-nuclear Alliance of West Australia (ANAWA). The original map tries to create a comprehensive visual representation of the nuclear industry in Australia, past and present. Significantly, given the close connection between the peace and anti-nuclear movements, the map also indicates the location of US military installations. Inset in the top right-hand corner of the map is a second map of nuclear shipping routes produced by Greenpeace Australia.

Maps are representations of particular understandings of space. Decisions about what to include and what not to reflect the map-makers’ understanding of space and how they perform that space. The nuclear mapping project undertaken by Ludlum and ANAWA takes aim at the invisibility of nuclear harm in the Australian landscape. It is a politically-charged cartography that emphasises Australia’s imbrication in the global networks of the nuclear industry and the close connection between civilian nuclear power and Australia’s subservient relationship to the United States military. The inclusion of nuclear shipping routes further highlights the transnational dimension of these nuclear sites. Of particular note for the IPP were the export routes that take uranium from Darwin and Adelaide to Japan and South Korea.

The 2002 map reflects ANAWA’s concerns and those of the anti-nuclear movement in Australia more broadly. It captures much of the knowledge of the nuclear landscape that had developed within the movement up to that time. If maps are performative political objects then there existence as two-dimensional representations come alive through spatial practices in three-dimensional landscapes. The IPP set out to walk this nuclear landscape, performing the cultural knowledge embedded in the map and tracing step by step the connections between some of its nuclear sites. Their footsteps would bring this cartographic understanding of the landscape to life.

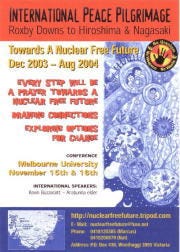

The IPP Conference

The IPP began with a two-day conference at Melbourne University in November 2003.5 Indigenous people took centre stage at the event. There were video messages from South Australian Indigenous elders, including Kevin Buzzacott and the senior Aboriginal women who make up the Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta. Buzzacott is a prominent Arabunna elder and anti-nuclear activist. He is a Traditional Owner of the Country where the Olympic Dam uranium mine is situated, and he joined the IPP for parts of the walk in both Australia and Japan. Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta was established in 1995 to protest Federal Government plans to dump radioactive waste in South Australia. Others addressed the conference in person. Speedy McGinness, a Traditional Owner of the abandoned Rum Jungle uranium mine in the Northern Territory, told the conference of ‘the pain he felt at knowing uranium from his land was used to construct the nuclear weapons that were tested at Maralinga and wrought havoc in the indigenous communities there’. He articulated the connection between uranium mining and nuclear weapons, and between his Country in the Northern Territory and that of Traditional Owners in South Australia.

Other prominent Australian Indigenous speakers included Kathy Malera-Banjalan, a traditional owner from Northern NSW, who outlined her successful campaign against gold mining on country and her involvement in the movement for a nuclear-free South Pacific. The conference also heard from Isabel Coe of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra, Sue Charles, Robby Thorpe and Dennis Walker. Speedy McGinness shared a message from Yami Lester, a survivor of the British nuclear tests at Maralinga and a prominent campaigner on that issue.

The conference was also a place of Indigenous internationalism, reflecting the growing globalisation of Indigenous people’s movements.6 Ainu activist Ponpeii Ishii spoke about the continuing discrimination faced by Ainu people in Japan, who were only officially recognised as an Indigenous people by the Japanese government in 1996. Ishii would later welcome the walkers on their arrival on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido by hosting an Ainu cultural event in Sapporo. Aurelio DeNasha, a Native American of the Ojibwe Nation also addressed the conference. DeNasha was a veteran of several spiritual runs and walks and provided a Native American perspective on the spiritual significance of walking.

Speakers from Japan also addressed the conference, including atomic bomb survivor (hibakusha) Satō Hōgyō and Japan Congress Against Hydrogen and Nuclear Bombs (Gensuikin) representative Inoue Toshihiro. Satō gave oral testimony about his experience of the bomb. Satō is also a Buddhist priest based at the World Peace Prayer Centre in Hiroshima (sekai heiwa inori no sentā), where he holds monthly multi-denominational prayer sessions for peace. As both hibakusha and Buddhist priest, Satō brought together two of the central cultural movements represented in the IPP: the Japanese hibakusha movement and engaged Buddhism.

Several non-Indigenous Australian activists also addressed the conference, including Senator Lynn Allison from the Australian Greens, Dave Sweeney from the Australian Conservation Foundation, and Jim Green and Loretta O’Brien from Friends of the Earth. There was a peace-focused session on the afternoon of the second day, with Tilman Ruff from Medial Association for the Prevention of War, Jacob Grech from OzPeace, Jeffrey McKenzie from Military Families Speak Out and Anthony Hannigan from the European Ploughshares movement. Atsuko Nogawa and Michizo Matsuzaki, who helped organise the Japanese leg of the walk, were among the last to address the conference.

I have listed the names of those who took part in the conference because it gives a sense of the shape of the anti-nuclear movement coalition that existed in the early 2000s. By that time, the Jabiluka struggle had subsided following the abandonment of plans to mine the deposit. Nuclear issues were no longer prominent in the social movement landscape, though the American war of terror and its invasion of Iraq with a ‘coalition of the willing’ in 2003 meant peace was still a very prominent issue. In this context, the Indigenous people whose lands were still being directly affected by the nuclear industry were keeping the movement alive through groups like the Alliance Against Uranium and later the Indigenous-led Australian Nuclear Free Alliance.

The conference was held in Melbourne. Widely regarded as Australia’s most left-wing city, the Victorian state capital is also the home to the national offices of anti-nuclear and environmental organisations Friends of the Earth and the Australian Conservation Foundation. Since 1990, Friends of the Earth and its anti-uranium collective had led the Radioactive Exposure Tours from Melbourne, taking city-based activists out to nuclear sites located far from major urban centres to forge connections with Indigenous communities impacted by these facilities. The tours evolved out of the Roxby Blockades against mining at Olympic Dam in 1983 and 1984, one of the first major anti-uranium struggles in Australia. The tours took visitors to the Mound Springs, a unique watering hole 120 kilometres north of Olympic Dam fed by water from the Great Artesian Basin that is threatened by the taking of water from the aquifer for mining. There they connected with Marree/Arabunna Traditional Owners. Later tours helped establish further connections with South Australian Indigenous peoples.7

The IPP conference was followed by it own Radioactive Exposure Tour-style bus trip conducted over ten days, that took activists to nuclear-related sites. Given the history of the tours and the importance of the Roxby Blockades to anti-nuclear culture in Australia, on 28 November 2003 the IPP then converged on the Olympic Dam mine in Roxby Downs to prepare for the start of the walk. Participants engaged in a seven-day fast at the mine site from 1–7 December before the walk began with a colourful ceremony and protest in front of the mine gates, which I will describe in the next essay.

The term freeter is a Japanese neologism formed through a concatenation of the English word free and the German word Arbeit (work). It emerged in the 1990s to describe the growth of insecure work, often with a positive connotation of being free from the oppressive strictures of company life. As Japan’s economic stagnation deepened and life for insecure workers became more difficult, these positive connotations largely disappeared.

William J. Nuttall, Nuclear Renaissance: Technologies and Policies for the Future of Nuclear Power (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2004).

Tim Collins, ‘International Peace Pilgrimage’, Green Left Weekly, 5 November 2003, https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/international-peace-pilgrimage.

International Peace Pilgrimage, ‘Mission statement, http://peacehq.tripod.com/OSIPP/IPP-RDH/rdh-mission.html, n.d.

My account of the conference is based on the following two post-conference write-ups by participants: Tim Collins, ‘Pre-Walk Conference Review: A Review of the “Exploring Options for Change” Conference’. Archived website. International Peace Pilgrimage - Content. (2005, July, 23) Accessed 23 Jul 2005, https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20050723015827/http://www.violet.com.au/html/modules.php?name=Content&pa=showpage&pid=8, 28 January 2004; Kaz Preston, ‘Meruborun Kokusai Heiwa Kaigi No Gohōkoku’. Kokusai heiwa junrei: kaku no nai mirai o omezashite. Accessed 14 June 2020, http://rainbow.or.tv/walk/kokusaiheiwajyunrei/03111516.html.

James Clifford, Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2013).

Ila Marks, ‘Nuclear Exposure Tours’, in 30 Years of Creative Resistance (Friends of the Earth Australia, n.d.), pp. 41–42.